From Paintbrush to Pixels with Neekhil Dighe

“As an artist, this film has shown me the value of Indian art styles and the role they played, and continue to play in our lives. They are our artistic roots and it is about time we explore these roots”, says Neekhil about his latest film ‘Bone of Desire’.

Neekhil Dighe is an artist, motion graphic designer, animation director, and communication designer currently working at Trip Creative Services. Growing up surrounded by artists and storytellers to creating his film under the banner of Folktales of India, Neekhil’s passion for storytelling and art is one fueled by his endless enthusiasm and curiosity. In today’s feature, we deep dive into his newest film, ‘Bone of Desire’ and the process behind it.

“Like many 90s kids, I grew up glued to Cartoon Network (with occasional scolding from family), playing with GI Joes, and constantly diving into DIY projects—sometimes pushing my family’s patience to the limit! ”

Born into a family that found joy in painting and performing theatre, Neekhil took a keen interest in animation. Joining the Model Art Institute and later L.S.Raheja College to study painting marked his introduction to Indian Art forms. Soon, he narrowed his focus towards animation at Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology where he was exposed to the craft of storytelling through films by iconic filmmakers.

Stepping into the industry through an internship with Arjun Gupte (Appy Monkeys Studio) he gained invaluable hands-on experience in animation. He later switched gears to work at Post Office Studios (Kulfi Collective), and today, he works as Communication Designer at Trip Creative services.

“I’ve wanted to focus more on filmmaking ever since I started working as an animator.” says Neekhil,” When I joined Trip Creative Services, Prateek introduced me to the Folktales of India project and asked me to choose a story.”

Folktales of India was the brainchild of Prateek Sethi; a concept that he imagined during his time at National Institute of Design. He aimed to recount Indian narratives as a series of Folktales, and later pitch to TV Channels like Pogo and Cartoon Network. Then deemed to be “too ambitious”, Prateek has now chosen to showcase these stories on Youtube under the ‘Folk Tales of India’ channel.

Each project in the channel was undertaken by students from various design schools across India or as a rite of passage for the team at Trip, dedicating approximately 4-6 months to the endeavor. This approach successfully blended passion with practicality.

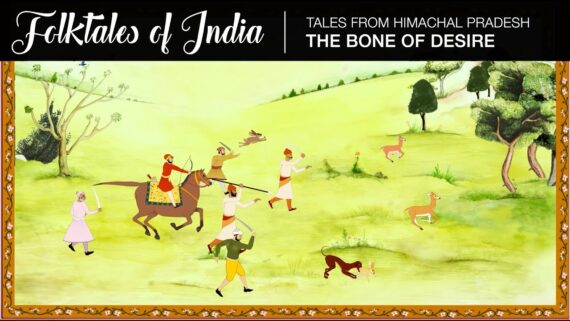

Each of the curated folktales have been selected from a region in the Indian Subcontinent, illustrated and animated in an art style native to the region.

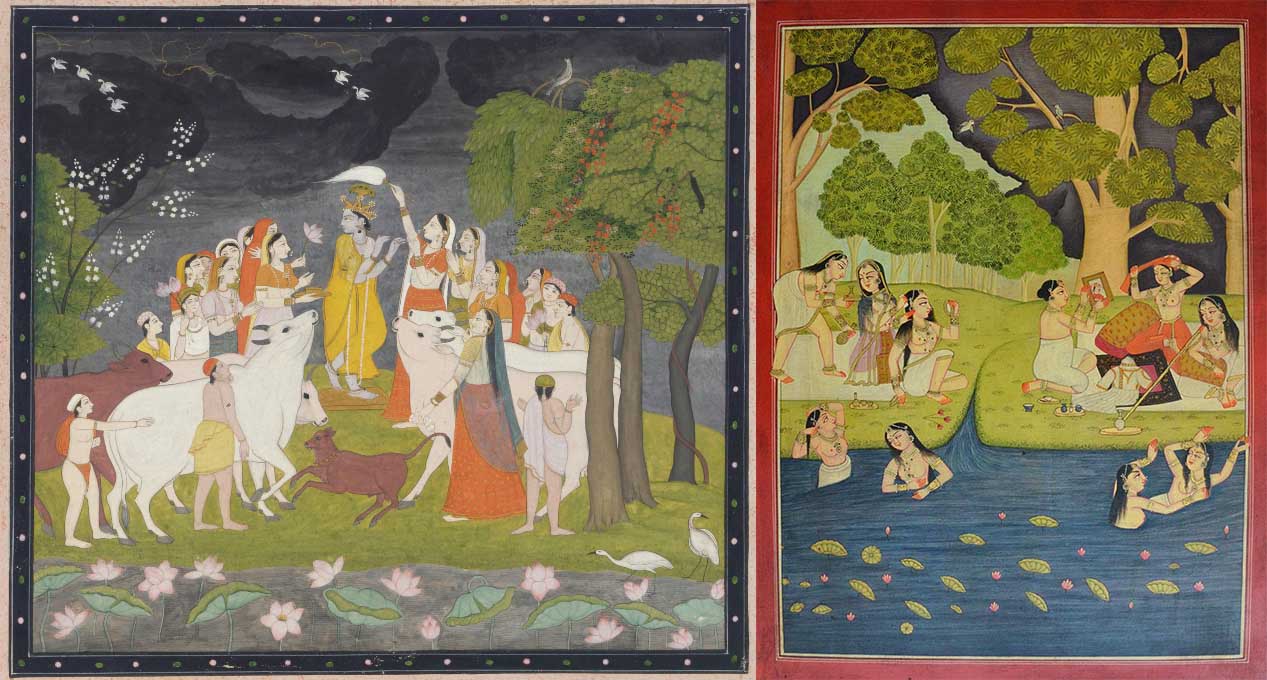

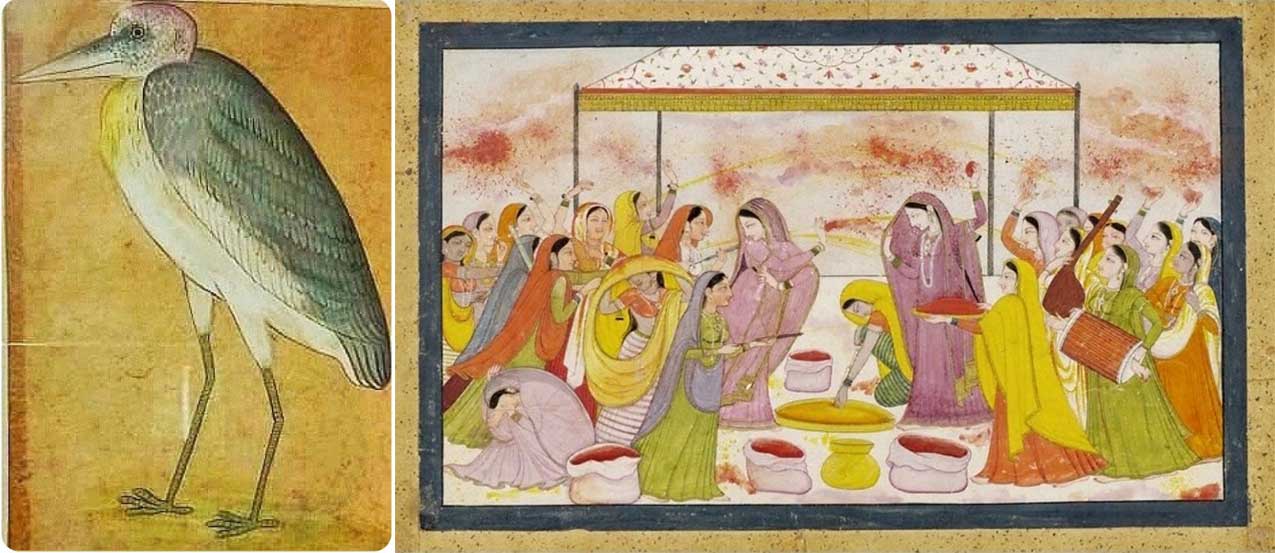

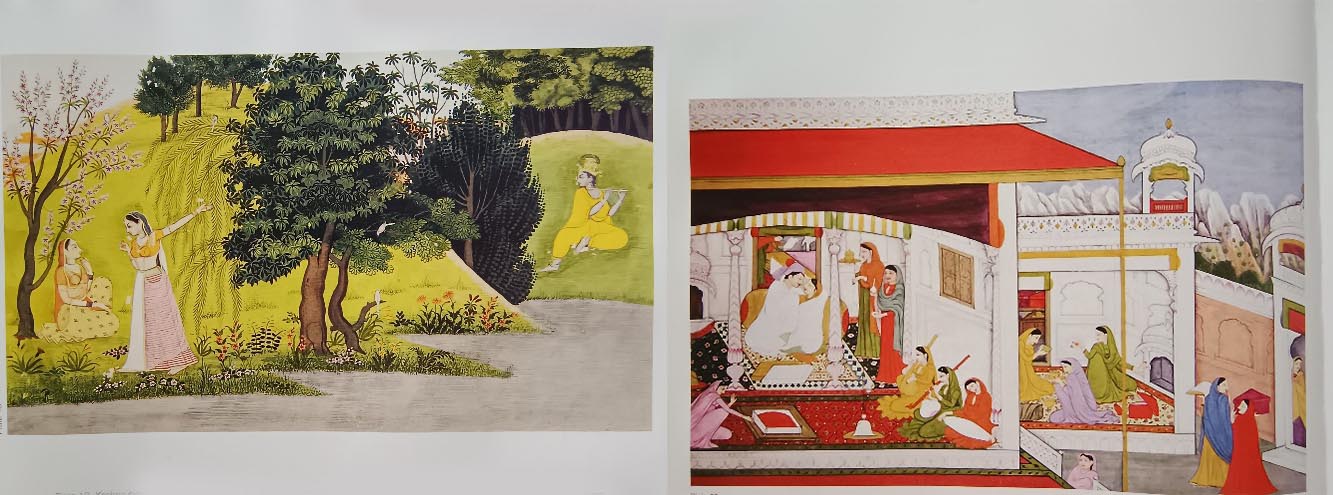

With a passion for traditional Indian art styles, in particular, Pahadi miniature paintings, Neekhil explored the folktales of Himachal Pradesh- the birthplace of the art style.

“My aim was to create fluid, mostly realistic animation while staying true to the Pahadi Miniature aesthetic. I’ve always believed that our Indian art styles have the potential to evolve into beautiful animated forms, and this project was the perfect chance to bring that.”

Among the many stories that he read was the ‘Bone of Desire’, a narrative that captures the restoration of a man’s relationship with others, with nature, and ultimately, with himself.

Neekhil says,” The message that sometimes one needs to step back and reassess their path, resonated deeply with me. The understanding that our actions, driven by endless pursuit of ambition and desire, are leading us astray is powerful and eye opening one. That’s why I felt compelled to bring this story to life”

While the task of crafting the intricacies of Pahadi paintings would startle a few, it was exactly these details that excited Neekhil.

He says,” I have always admired how Japanese animations, particularly in the works of Hayao Miyazaki, have evolved their traditional art forms into animation. Despite this evolution, they have managed to preserve the essence of their traditions.”

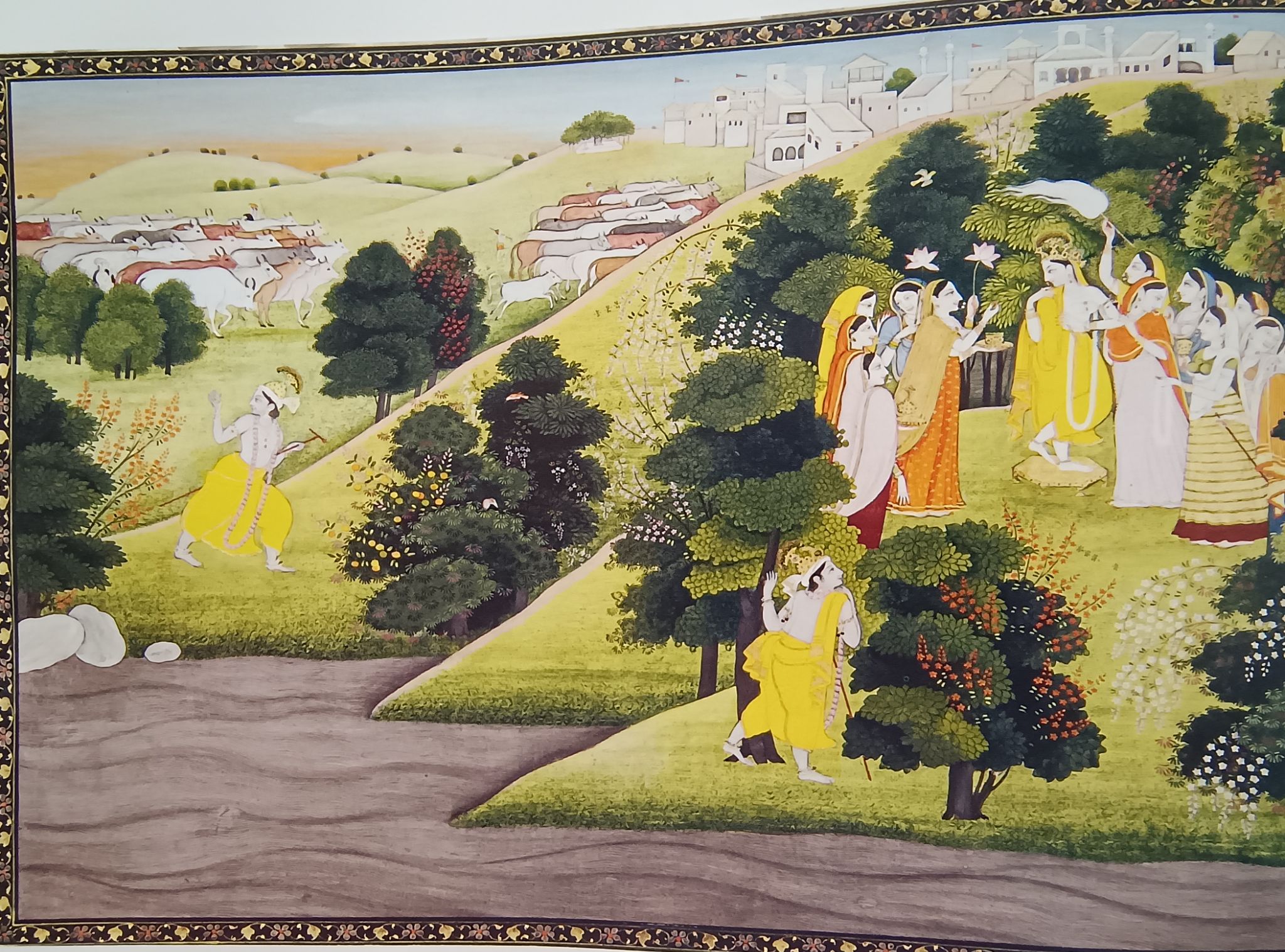

“Through studying numerous paintings, I observed the meticulous detail, grace, and storytelling in Pahadi Miniatures. Each element, from a distant bird in a stormy sky to a small tree by a river, contributes to the artwork's narrative.”

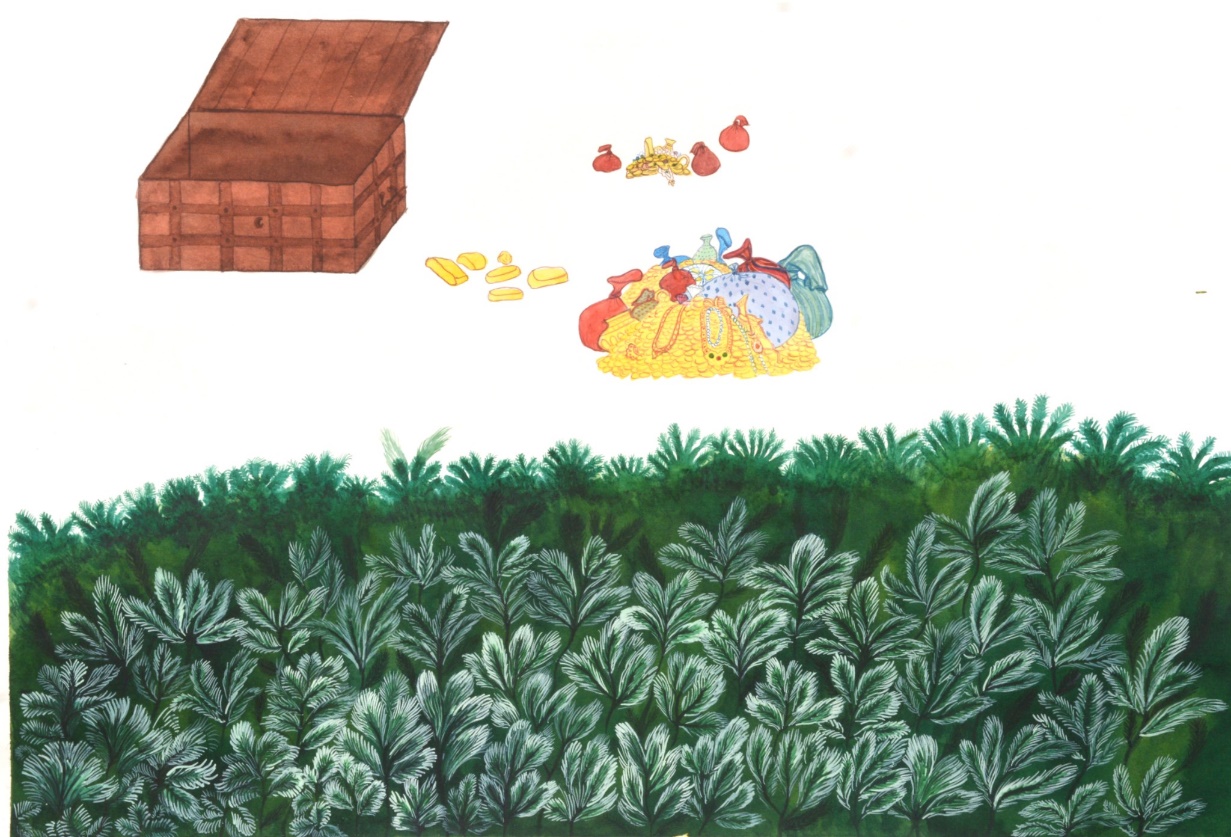

Armed with a deep understanding of the art form, Neekhil was ready to craft the film. Given that the style demanded a traditional paper-based artistry and the animation followed a digital pipeline, Neekhil decided to hand-paint the backgrounds- a process that was guided by extensive research.

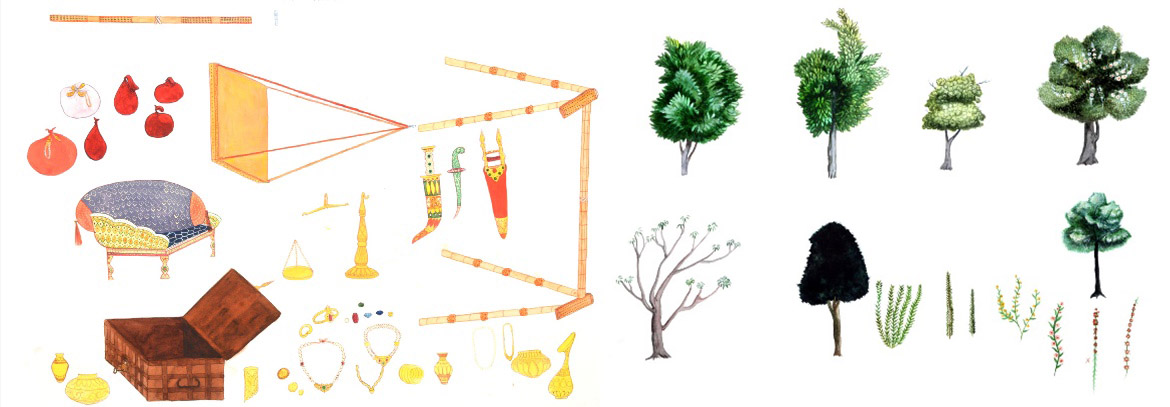

“I began by listing out the backgrounds, their extensions, the various types of trees, and other assets that needed to be painted separately. These elements would later be combined digitally.”

With the help of John Varker’s voiceover he drafted a rough thumbnail board to assess the length and complexity of the film.

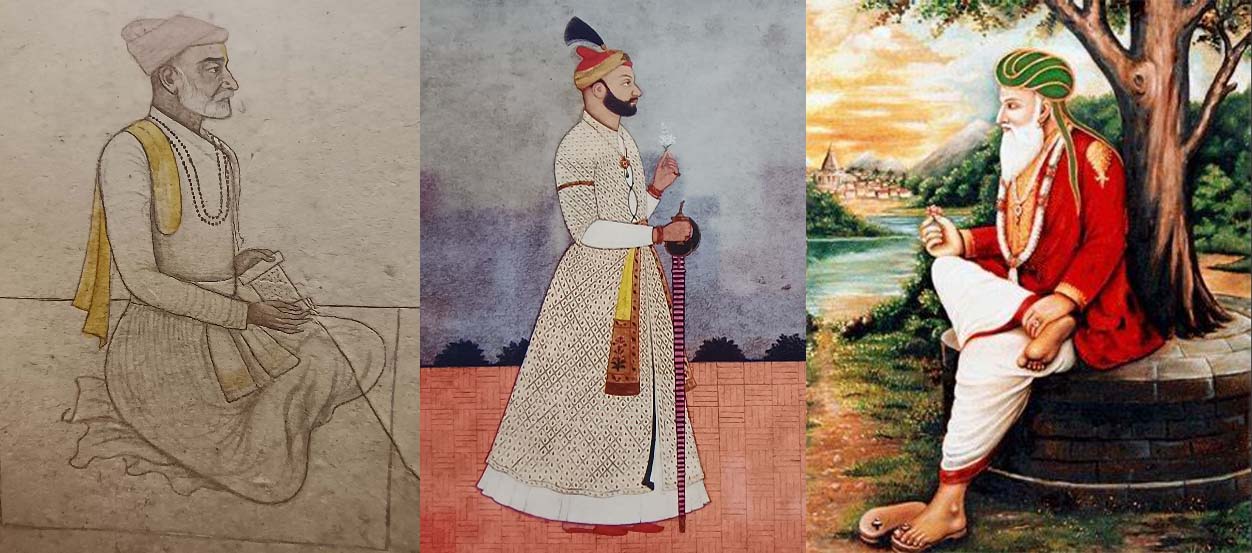

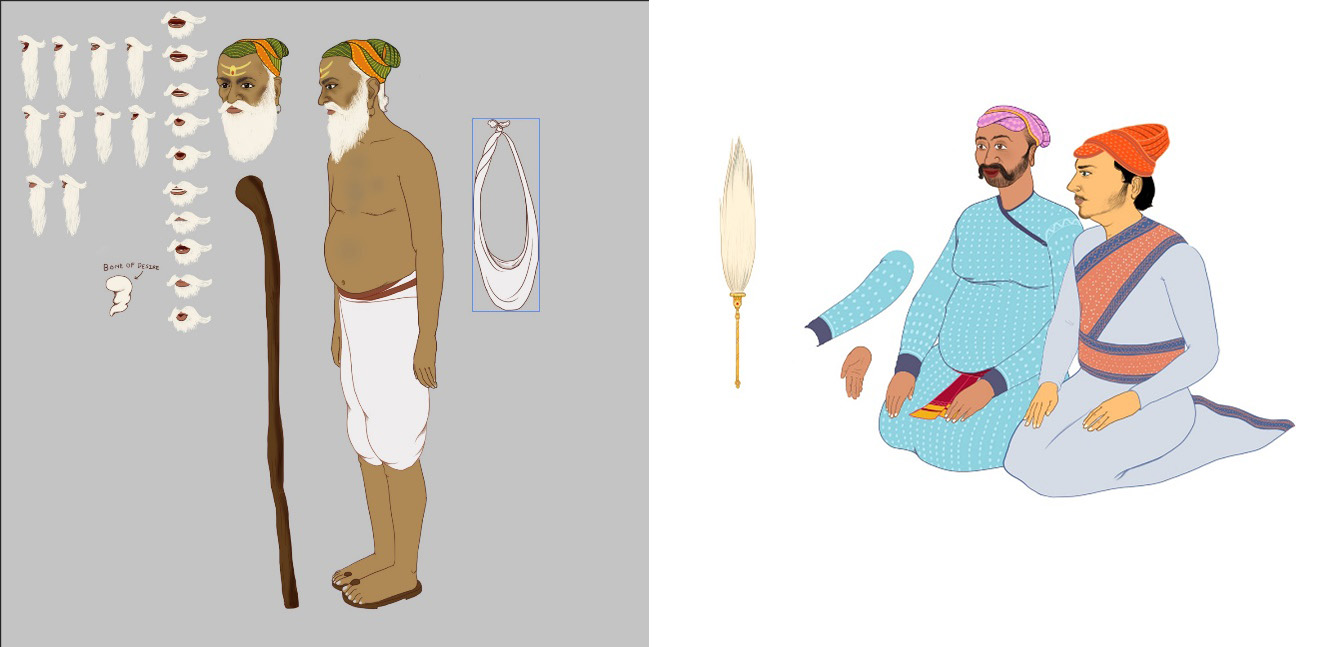

This was followed by the meticulous and time-consuming process of hand painting all the backgrounds. Simultaneously, he worked on character development starting with the main characters, such as King Udaygiri, Old man, courtiers, animals and birds.

He relied on high-quality watercolors like Winsor & Newton and Fuji Water Folios, and, used the smallest of brushes for precision in the pattern and lines.

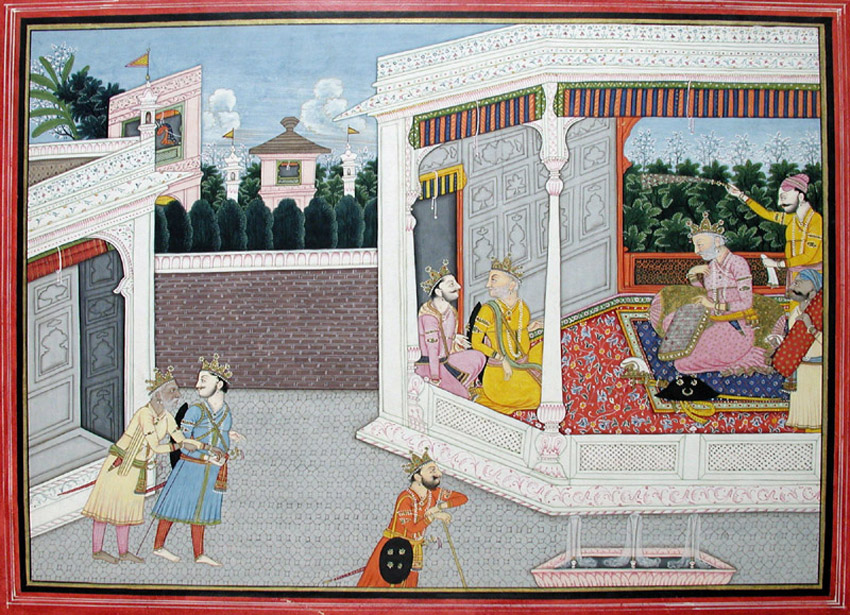

“In the town shot, the clusters of houses and their intricate detailing needed to be precise in both perspective and detail. I realized that Pahadi Paintings use multipoint perspectives and variable scales, while maintaining the freedom of glorifying the focused subject.”

Neekhil however approached the character design digitally. He borrowed the essence of the hand painted elements to the character design for a cohesive look.

The challenge he faced was of making the character fit into their environment; whether it was the elaborate marble interiors or the front lines of combat.

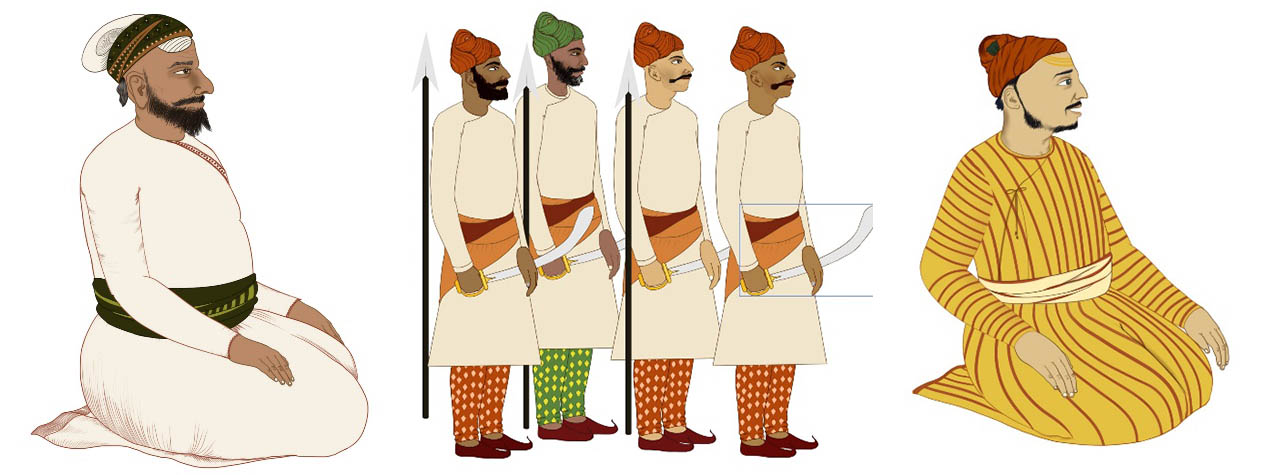

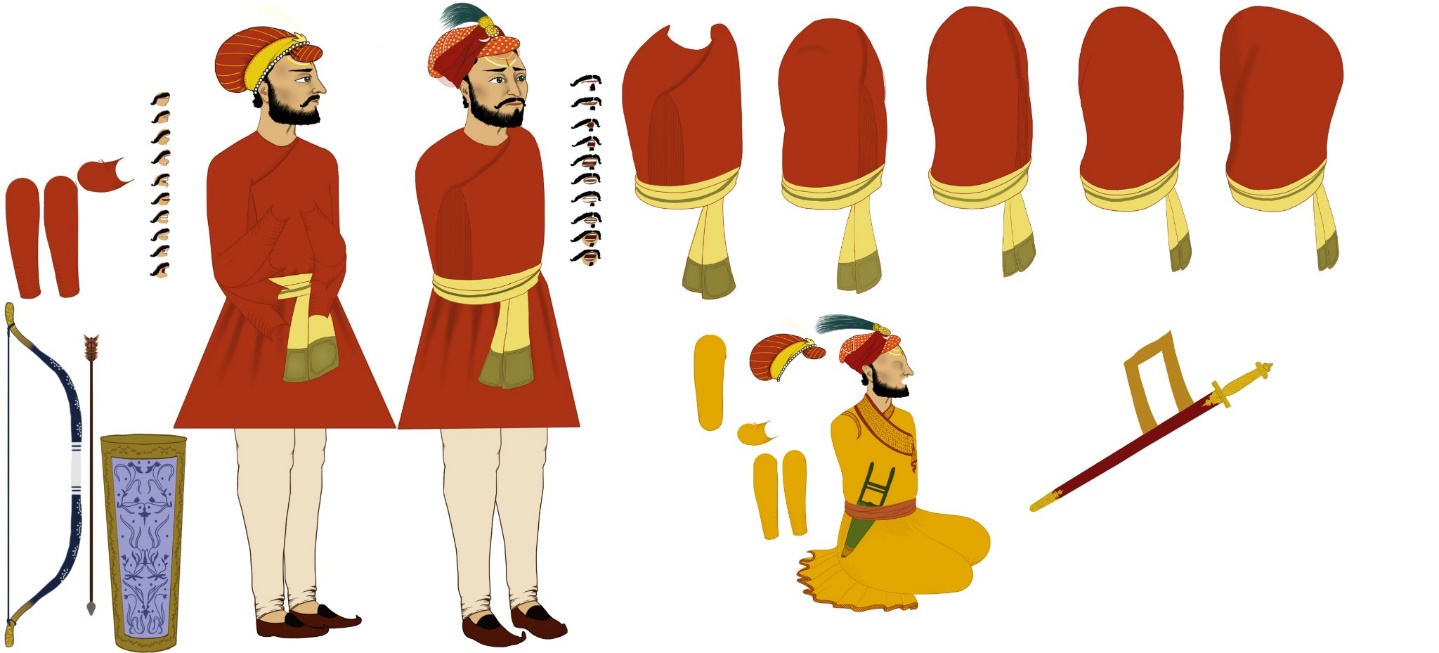

“Whether designing courtiers or villagers for the war sequences, I approached each character as a detailed portrait. This perspective transformed my approach to character creation.”

He used Photoshop to create the characters and rigged them in After Effects; provided Neekhil the flexibility he aimed for.

While creating the characters he also created the different lip shapes for lip sync to later animate with the voice overs. One of the characters, King Udaygiri required two versions: one for the hunt and one for court scenes.

“The amount of assets really depended on the amount of actions and animation each character had. This bifurcation really helped speed up the process.”

“Like for example, I had to make different arm shapes and torso twist shapes for the king to do the action of shooting an arrow. For his water drinking shot I had make forearm shapes and proportionate palm shapes to make him drink water.” Neekhil adds.

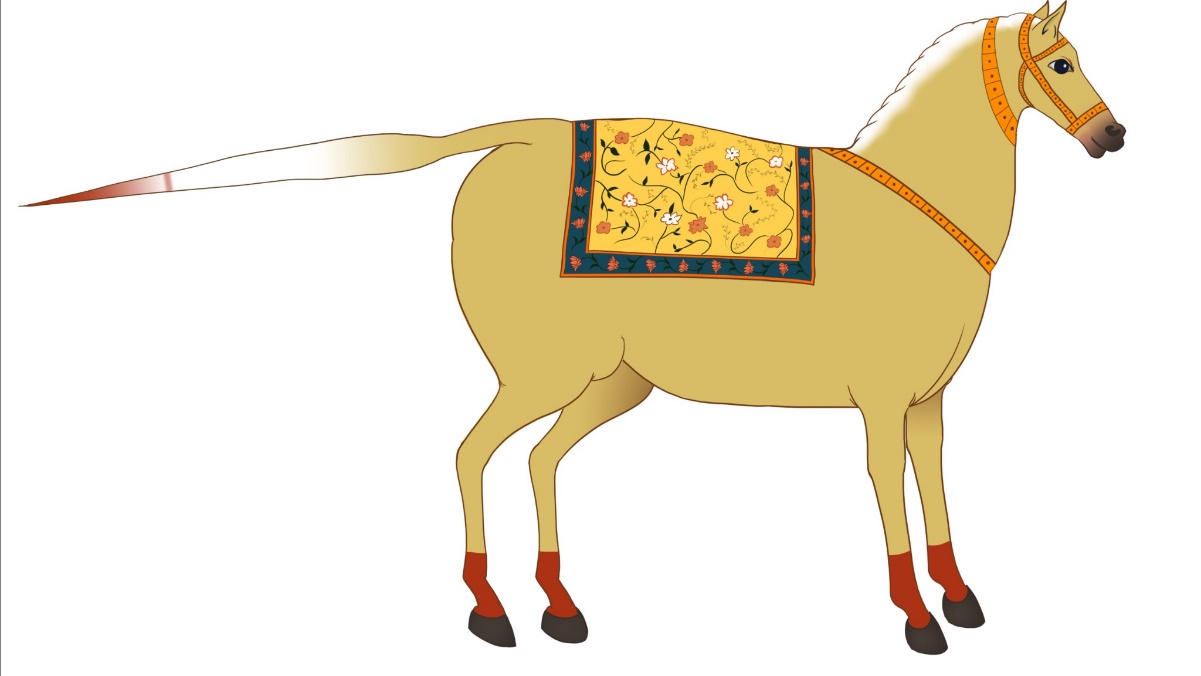

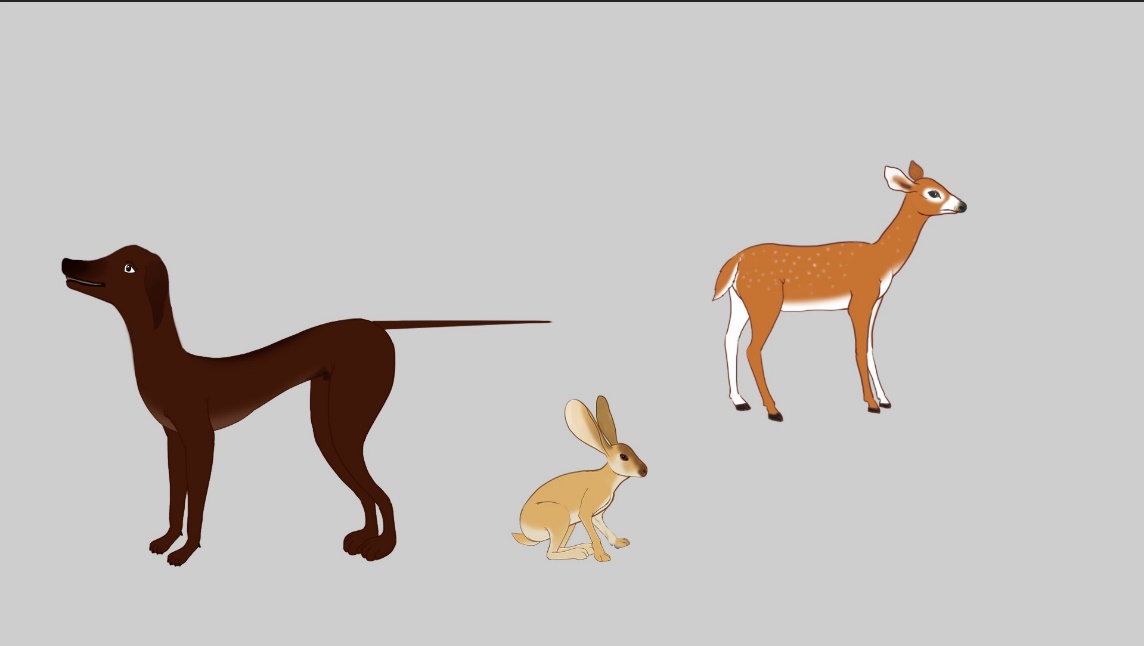

Then he created other characters, including animals like elephants, horses, birds, and cows, as well as characters for the war sequence, which were also used in the town’s full shot. Neekhil studied the weaponry of that time, including the "Gophan" or sling, to differentiate between the king’s army and the villagers. Despite being digital, all characters were painted manually and, right cohesive patterns were made to integrate them seamlessly with the hand-painted backgrounds.

Rigging some the animals in the film allowed Neekhil to develop an eye for quadruped animation. The synchronization of the steps was something that had to be understood by studying the weight shift.

“I had to look at a lot of references of horse and elephant run and walk cycles along with their idle behaviours. Drawing these out sometimes in stick figures also helped quite a bit to understand the sync of their leg movement and the consecutive body movement.”

One of the most spectacular parts of the film includes the war sequence. Every character was detailed to perfection. Neekhil conceptualized these motions through acting out the movements. Without acting the characters would have looked artificial in their actions.

Neekhil captured the fierceness of the battle by creating small action sets that could be added to the final war sequence. He detailed out the smallest elements like The King’s strategic use of infantry, cavalry and elephantry, and the villagers’ resourcefulness and chaotic approach.

“These smaller sets of animations made my process faster and smoother, as I didn’t have to deal with multiple characters in one shot, also saving a lot of the rendering time.” Neekhil says.

“Figuring out a systematic process and then sticking to it no matter what, has been the key.”

While regular animation allowed for multiple ways to adjust the camera, Neekhil refrained from using this technique to preserve the authenticity of the Pahadi Miniatures .This meant there were more animated elements to be crafted that maintain continuity through the narrative.

Towards the end of the production, the digital, hand painted and VFX elements had to look cohesive yet pay homage to Pahadi Miniature Art. Hence, color grading was definitely something that required attention.

A lot of research also went in the bird sounds and the musical instruments that were used in Himachal Pradesh, like Karnal, shehnai, dholku and Nagara. The usage of trumpets for the war sequence, the nagara and flute was beautifully done by sound designer, Rahull Raut from Hooch Studios. Neekhil adds, “He made this beautiful sound design, incorporating elements of foley with the music that stays true to the region and the era.”

Neekhil believes that Indian art forms and folk art is a massively unexplored treasure trove. Creating this film has opened Neekhil’s understanding of painting beyond the impressionist styles popular today.

“I have learnt that to create something really artistic in its approach there are no shortcuts and no cutting corners. It requires meticulous craftsmanship, learning and inquisitiveness to actually grasp lifetime’s worth of work and get it into an animated film. All the backgrounds, assets, sequences and animations, have been a joyride full of stories and processes that are stored in my heart forever.”

On that note we come to the end of this feature with Neekhil Dighe. He extends his heartfelt gratitude to his family, friends, teachers, Prateek Sethi, and Trip Creative Services who have always supported him through this endeavor.

Today, Folktales of India has over 9,000 subscribers and more than a million views on YouTube. The numerous encouraging comments that pour in make creators like Neekhil Dighe and producers like Prateek Sethi feel rewarded for their efforts in bridging the gap to understanding our cultural heritage—it’s what keeps them going!

Neekhil’s hot take on GenAI

Generative AI and Machine Learning, like all other previous technologies, are tools. It is upto the user as to how they use it. It has made a lot of processes simpler and faster, but at the same time, one cannot depend on them to give a 100% output. Human touch and mind is required.

I have used it countless times in VFX to aid my processes. But as an artist, I would very much like to use my intelligence, understanding and most importantly my skills to create films and artworks. Because it is a choice on a personal level whether to use it, or how much to use it, I would say that I would integrate it as much as it is needed to be (if at all) in any given project. 🙂

We wish Neekhil all the best for the future and hope to catch him on his next release. Until then, you can stay updated with his work on the channels below:

Neekhil Dighe